“So, what do you like about Trump anyway?” I asked my dad one evening during dinner.

“I like Trump’s policies, he has really boosted our economy. Biden has made it worse than ever,” he said.

“But he’s racist! He’s also… bad too,” I replied.

“The most important thing is that we survive. I would choose him over other presidents,” he argued.

“You’re just a pig then. You don’t care about our rights or being treated fairly, you just want to be able to eat and sleep,” I complained.

Other than a ruined dinner, this event has caused me to reflect on my political views as a Gen Z teenager and how they came to be. Why do I dislike Trump? Because he’s racist? Do I know anything else about him? What about Biden?

Reflecting on this situation, I realized that I did not know much about the two candidates running for president, nor did I consider my parent’s point of view when confronting them about their political views. Economic figures like the S&P stock’s 42.3% increase during Trump’s presidency, recent political events such as Biden’s support of workers unions, Trump’s explicit language during the 2024 campaign, or popular controversies like Biden’s increasing age were unknown to me. I was told that Trump was bad, and Biden was… Biden.

Moreover, as Asian immigrants who grew up in poverty, my parents are more sensitive to changes in the economy and agree with the 65% of people polled on CBS News who remember Trump’s economy being “good.” In reality, according to data from CBS, the fluctuating inflation, wage, and interest rates during Biden’s presidency mainly stemmed from the COVID-19 pandemic and not his ability as a president.

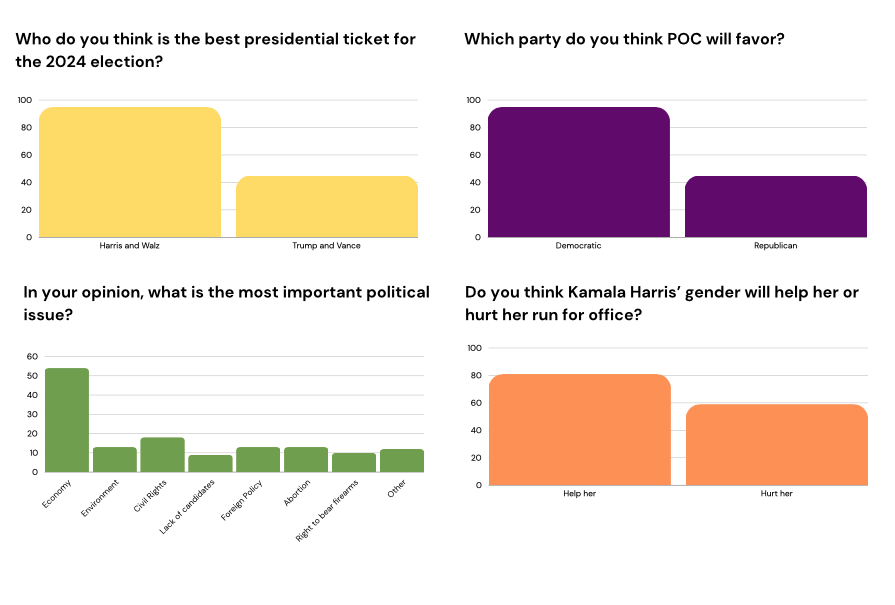

As an average student at Mt. Eden High School, who reads the news 4-5 times a week and occasionally listens to news channels like CNN, CBS, and FOX, I am still largely uninformed when confronted with politics. However, I am still inclined toward supporting the political left, and the Democratic Party. This has led me to wonder how I have such strong opinions with little information, and what the effects of this contradiction are.

If we take a broader look at our Hayward community, we will find that we are inherently a blue state, meaning democrats win most elections in the state. The main Democratic values are equal rights and representation for all people, worker’s rights, and government involvement. Correspondingly, Mt. Eden has a large ethnic minority community, with most families being low-mid class. US News found that ethnic minority enrollment of MEHS is 97%, and 47% of students receive financial aid and free lunch.

This system reflects in the entire Bay Area. KQED found that “registered Democrats far outnumber Republicans,” and that “more voters registered no party preference than Republican.”

Thus, there exists an implicit “bias” against Republican values around campus: whether that be a general dislike for guns during class discussions, the inclination toward supporting worker unions or social welfare programs, or the stone-faces and instinctive feeling of repulsion when talking about Trump.

But we cannot accurately define this influence as a bias, an “unfair prejudice in favor of or against one thing.” The basis of democracy allows people to favor political representatives or programs as they align with an individual’s interests. Therefore, politics is really built on individual preference, whether that preference stems from one’s childhood or adulthood.

While it’s not unfair, this childhood predisposition can feel confining to many students and can potentially become problematic as they become adults. Internally, you may feel that you have heard the same political viewpoint from parents and teachers as long as you’ve lived, inciting an uncomfortable doubt that your opinions and political views, from how to manage your time best to who you favor as president, are not truly your own. To others around you, it can feel like trying to persuade someone who is so fixed in their ideas that they completely shut you off and just “wait for their turn to talk.”

Adult Americans see this problem everyday in the wide political split between Republicans and Democrats, such as the tug-of-war during potential government shutdowns every few years. Since communication is such a large factor in politics, this natural predisposition could contribute to the cycle of discomfort and confusion between the two political parties.

To make sure that students do not leave highschool with a solidified/hardened political perspective, teachers and students are left with significant questions of how to consider politics effectively.

Should teachers share their political opinions with students? Diana E. Hess, the dean of UW-Madison’s School of Education, defines this as the “teacher disclosure question.”Some experienced teachers like Willian Bigelow and Robert Peterson believe that trying to remain neutral is unrealistic and “irresponsible.” They argue that valuing “truth, rather than balance” will develop better morals within their students. Other teachers recognize the significant power teachers have over student’s opinions, and don’t disclose their opinions because they “don’t want kids to agree with [their] views just because [they are] the teacher.”

According to Hess, the four main ways teachers’ political views affect students are denial, denying that an issue is controversial/arguable, privilege, giving more attention to a perspective they know to be right, avoidance, avoiding controversial political issues altogether, and balance, teaching ALL sides of an issue no matter its legitimacy as an arguable topic. MEHS has experienced these influences before: specifically the outrage over Mr. Ben’s teaching of antisemitic texts, which can be seen as “Balance” teaching.

Should parents talk to kids about politics? Cambridge University press explains that children who are exposed to and likely adopt their families political views tend to become “politically engaged adults.” This engagement, ironically, increases the likelihood that these now-grown-adults variate from their parent’s original ideologies. It seems then that teens should communicate with their parents on politics, as it will likely develop their political individualism and freedom in the future.

Most importantly though, how should students engage themselves in politics? As a student at MEHS, I believe that our role as developing adults should not be to solidify our pre-existing political views but to mold and expand upon them, even if “expanding” means learning about unpopular or uncomfortable political views.

To clarify, there isn’t a need to “balance” ourselves or to “fix” our inherent preferences. What should be changed is both our political discourse in MEHS, which seems to be centered around democratic ideals, and our awareness of these preferences. Why do you dislike Trump so much? Specifically, how much government involvement are you comfortable with in day-to-day life? What really makes you uncomfortable about disagreeing with worker unions? Or giving aid to Ukraine? Reflecting on these questions and trying to apply them to the political discourse at MEHS will prevent students from confining themselves within the boundaries of the ideals they grew up with.